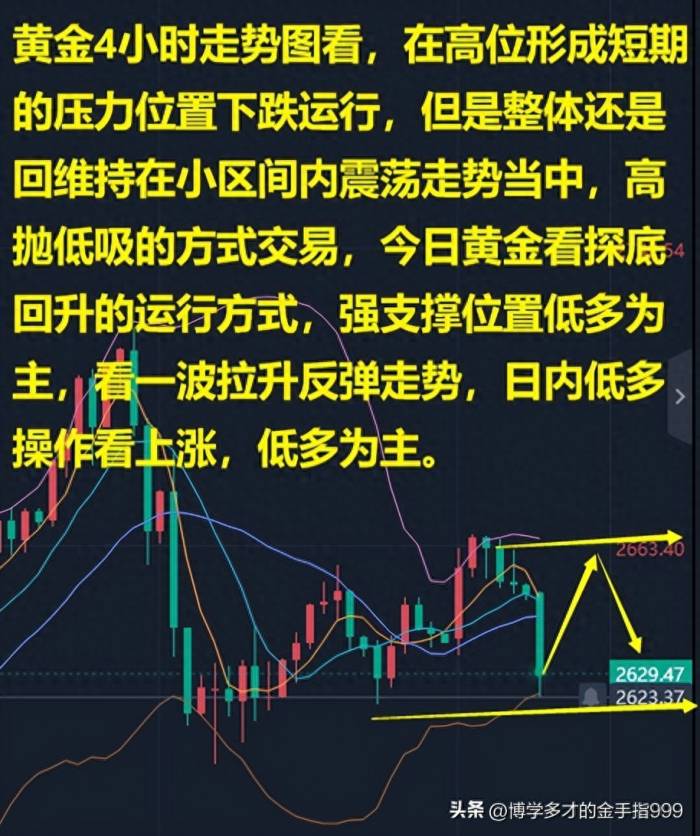

The prevailing sentiment among observers is that after a protracted four-year period of interest rate hikes, the Federal Reserve has successfully met its goal of curbing inflation in the United States. The anticipated next step would be a shift toward lowering interest rates. Jerome Powell, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, even suggested in late August that the time had come for rate cuts, which significantly boosted market confidence at the prospect of a monetary easing that could provide a sense of relief worldwide.

However, as time progresses into September, the eagerly awaited announcement regarding rate cuts has yet to materialize, leading many to speculate whether this notion of lowering rates is merely a "tactical" maneuver by the Fed. Concerns are mounting that the anticipated changes will not occur as expected.

Beginning in 2020, the Federal Reserve embarked on an aggressive path of interest rate increases. In July, they raised the interest on dollar savings by another 25 basis points—a seemingly modest adjustment—but it marked a significant moment in economic history, being one of the highest rates since 2007. The Fed's goal of pushing the benchmark interest rate from an existing 5.25% to 5.50% brings into question whether this approach could potentially crush a major economy.

As the sole superpower in the contemporary world, the United States has fundamentally redefined the global landscape since the end of the Cold War. The dollar’s supremacy has established a framework for global economic order, allowing the U.S. stock market to serve as a barometer for economic conditions worldwide. When the U.S. opts to increase interest rates, it inevitably causes an influx of private capital from other countries into American banks, where the allure of interest accumulation far outweighs the risks of venture capital investments.

Furthermore, should the Federal Reserve eventually decide to cut rates, other nations may only sustain minor losses in interest, rather than completely losing their investments. However, the ramifications for other countries can be dire. The outflow of liquid capital signifies a considerable decline in national investment shares and a sharp reduction in foreign exchange reserves. The absence of this "hot money" can precipitate economic crises, while inflation initially observed in the U.S. starts to ripple through other countries.

In response, the U.S. and several Western nations with substantial dollar holdings will act swiftly to capitalize on the high value of the dollar, whisking away valuable assets from these countries and potentially short-selling foreign currencies. After this wholesale acquisition, the Fed would then initiate a rate cut, leading to the depreciation of the dollar. This scenario allows U.S. financial capital to repackaged and resell assets, reaping a greater volume of dollars than previously realized, triggering a currency repatriation cycle that strips foreign reserves from other nations.

While tight monetary policies wield certain advantages, they also bear inherent risks. One might wonder why the U.S. does not simply remain in a perpetual cycle of tightening interest rates, potentially destabilizing the global economy and ensuring that America could enjoy uninterrupted prosperity. The underlying truth is rather simplistic: the U.S. itself is grappling with an astronomical national debt that has now surpassed $35 trillion.

As interest rates rise, the U.S. dollar appreciates. This escalates the interest obligations owed by the American federal government on its national debt, leading to global economic distress in a situation where the U.S. suffers considerably too. The banks in the U.S., while benefiting from an influx of global capital, are likewise under considerable strain due to the monumental interest payments they must provide to depositors.

The American banking system's historical reliance on high leverage complicates the situation further, as prolonged reliance on this strategy could lead to financial strain, risking a chain of bank failures reminiscent of the Great Depression of the 1930s. Unlike then, when World War II helped absorb excess capacity in these industries, today’s nuclear arsenal serves as a deterrent in global conflicts, disallowing the U.S. to directly provoke a world crisis without severe repercussions.

From a purely tactical standpoint, the Fed's interest rate hikes and subsequent cuts ensure the United States maintains operational control over its "nuclear-powered money printing machine," affording arbitrary wealth generation. However, years of fiscal irresponsibility by successive administrations since the 1990s have effectively created a monumental ticking time bomb within the American financial system. Currently, the specter of a staggering $1 trillion in annual interest payments looms over the national budget.

To be blunt, the U.S. federal government has unwittingly transformed into a "bad ally" for the Fed, obstructing American efforts to harvest the world's wealth by funneling a sizable portion of the “hot money” reclaimed from interest hikes to relieve its own debt burden rather than investing it back into acquiring prime foreign assets.

This cycle highlights a critical dilemma; the $35 trillion debt cannot be settled overnight. Historically, U.S. presidents have adhered to Keynesian principles, often subscribing to a mindset of "I'll be dead when it happens." With the principal amount of these debts remaining stagnant, the only recourse has been to borrow anew, perpetuating the cycle of "new debt paying off old debt."

Expenditures appear significant when viewed superficially but, when adjusted for inflation, reflect a substantial decrease when compared to previous decades. This reduction holds far-reaching implications, striking at the very core of federal policies and inherently stunting American advancements in scientific research. For the past 30 years, the strength of the American economy has derived largely from its unrivaled superiority in research, which translates into considerable yields that underpin its position in the global value chain.

Today, however, the U.S. finds itself ensnared in the pitfalls of deindustrialization, resulting in sharply declining investment in research and development. An alarming indicator of this decline is the diminishing deterrent effect of the U.S. military; evidenced when a relatively minor group, such as the Houthis, can easily disrupt Western interests. Not so long ago, American forces confidently confronted the "third strongest military power" over supposed slight, quickly overpowering their adversary using extensive military superiority. Now, the inability to engage meaningfully belies a deep sense of unease regarding American prowess.